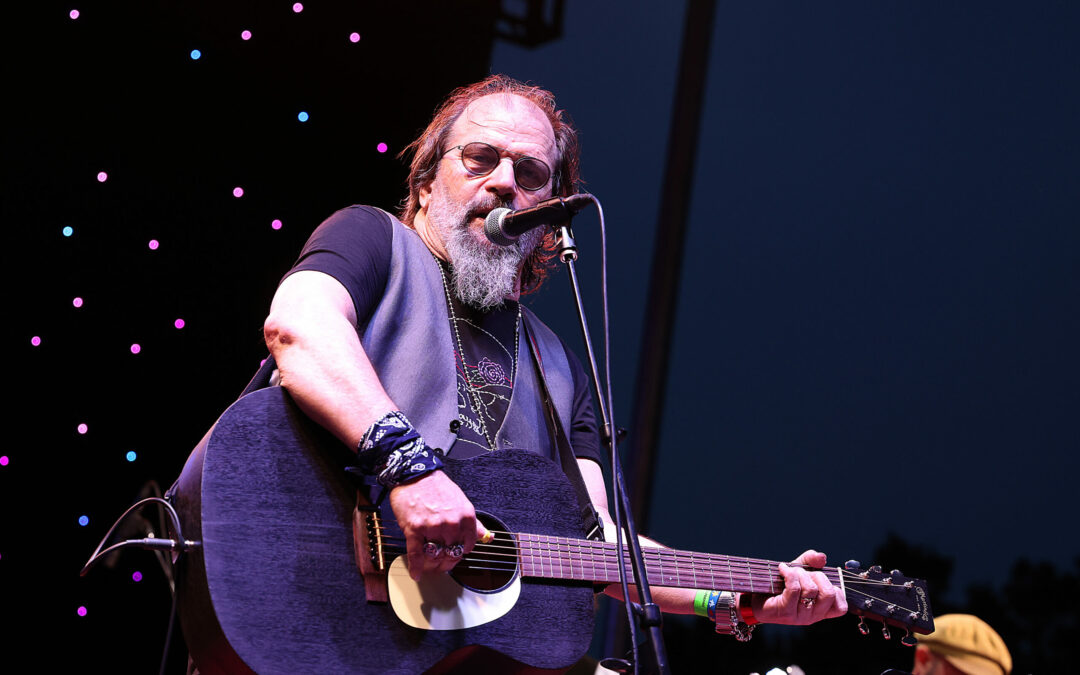

Steve Earle adds, “I’m hoping to get songs on country radio.” It’s hardly what you’d expect to hear from Earle these days, especially since we’re talking about Jerry Jeff, his new tribute album to Texas superstar Jerry Jeff Walker from the 1970s.

Earle is deadly serious, even if the prospect of a mainstream country smash makes him laugh. Nothing has the 67-year-old singer-songwriter more excited than Tender Mercies, the 1983 film about a down-and-out country singer he’s spent the past years working on after the end of his nightly appearances in the off-Broadway play Coal Country — prepping for a tour with the Dukes, working on a novel, awaiting word on a TV pilot that’s “a science-fiction thing set in Marfa,” covering the Grateful Dead’s “Casey Jones,”

Earle says he needs to write a number of songs for the play’s imaginary band that would fit on a modern country playlist for narrative purposes. “If I can write something for them that you might hear on country radio right now,” Earle says, referring to the successful Broadway musical-turned-Hollywood smash Dear Evan Hansen. “That is the plan.” It’s been meticulously calculated. Before I die, I want to have a Broadway success. That’s what I’m attempting.”

To learn how to master today’s country, Earle has been writing with a slew of Nashville songwriting pros like Travis Hill (Kenny Chesney, Chris Janson) and his favorite young newcomer, Elvie Shane, with whom he’s about to record a version of “Pancho and Lefty.” He also mentions a song he’s started with Miranda Lambert that they’ve been sitting on for the last two years. “I’m trying to get her to finish a fucking song,” he says.

“The money would be wonderful,” Earle says as he daydreams about landing a country No. 1 in his New York studio. “However, I’m not so egotistical as to believe I know how to [write] like that.” Folks made fun of me a few years ago by claiming that country music is primarily hip-hop for people who are terrified of Black people.” (The Earle one-liner was taken from a 2017 interview.)

“However, that was not a disparaging remark,” he continues. “It was just a logistical statement.” It was more of a tribute to hip-hop than anything else, but it wasn’t meant to be offensive. “Hey, what these guys are doing isn’t country,” I’ve never been one to say.

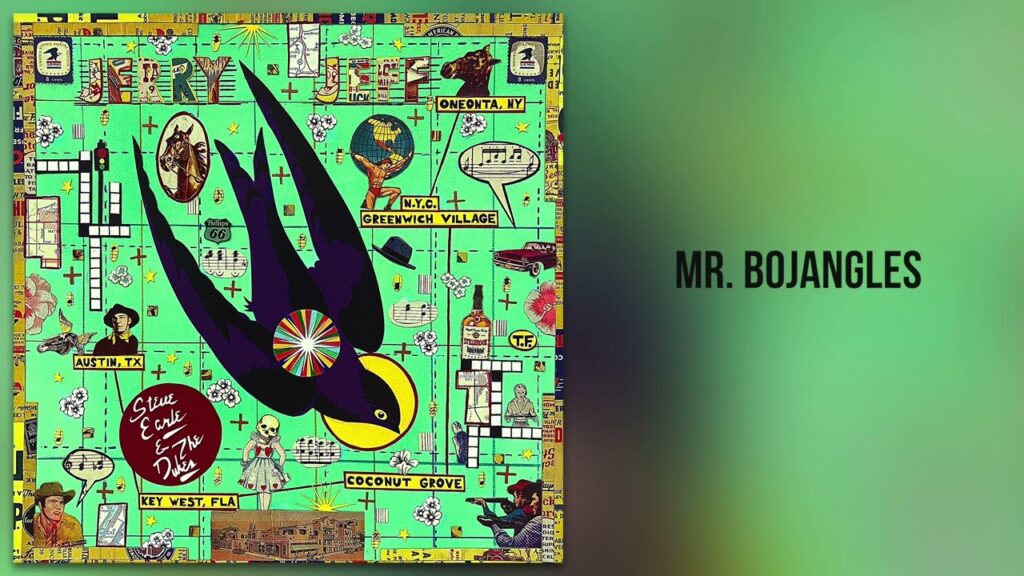

Earle will spend the summer touring Jerry Jeff before returning to work on Tender Mercies. Earle’s fourth tribute album (and third in the last three years), it’s a homage to the “Mr. Bojangles” songwriter, following 2009’s Townes, 2019’s Guy, and 2021’s J.T., a heartfelt memorial to his late son, Justin Townes Earle. Earle said of his tribute albums, which have all occurred after the death of a close friend or family member, “I hope I don’t produce another one.”

So, how did Jerry Jeff come to be, which sounds like the most natural, free-flowing Earle record in years? Earle claims there are two explanations, one of which is less poetic than the other. Earle, on the other hand, admits that he “kinda needed a record this summer” and that he is far too engrossed in musical composition to have enough original material for an album. But, more kindly, Earle’s passing in 2020 had gotten him thinking about Walker’s influence on his own life — how everything, including his well-documented respect for Townes Van Zandt and Guy Clark, can be linked back to the Texas-via-Oneonta, New York, songwriter.

Earle states, “I was a lot closer to Townes and Guy, but I would never have learned about them if it hadn’t been through Jerry Jeff.” “Jerry Jeff Walker was singing a Guy Clark song the first time I heard it.” It didn’t make sense to me not to release this album. That just felt like a lack of regard for my elders, and my respect for my elders is probably the best fucking element of my character. “Nearly everything else is debatable.”

Earle relishes the chance to talk about Jerry Jeff and share stories about another bygone legend from his past. Asked what he thinks people don’t know about Walker, he speaks for an uninterrupted eight minutes: He talks about how Walker once destroyed Earle’s guitar just months after buying it; how Jimmy Buffett recently told him that inviting Walker to stay at Buffett’s home years ago “finished off his marriage”; how Walker and Earle got much closer in the last few years of Walker’s life after his cancer diagnosis; how Walker introduced Earle to Tom Waits’ music; how Earle’s feelings are still a little bit hurt, decades later, by the fact that, when Walker once woke him up in the middle of the night to play a song for Neil Young, he asked Earle to sing one written by David Olney instead of one of his own.

Earle hopes his Jerry Jeff album reinforces the main point he wants to make about Walker — that he never received enough credit as a songwriter. Walker’s most famous recordings were often other people’s songs. “‘Mr. Bojangles’ was not the only great song he wrote,” he says. “I wanted to make sure people knew that.”

Earle is only more enthusiastic when discussing theater than when paying tribute to Walker. He’s been watching as many plays as he can recently, including musicals, dramas, and anything else. He recently saw Macbeth and is about to see David Mamet’s American Buffalo (“It’s a girl who wants to go see it”). Earle praises Bob Dylan’s musical Girl From the North Country, partly because he sees it as a precursor to the type of hit musical he hopes to compose in Tender Mercies. He argues that 50-year-old ladies are the ones that buy concert tickets. “However, 50-year-old women grew up listening to Bob Dylan, so here is my chance.”

Earle cites another piece he hopes to see soon: Paula Vogel’s How I Learned to Drive, the most recent Broadway production. He adds learning the cast has been walking out to Justin Townes Earle’s “Champagne Corolla,” a song he covered for last year’s J.T.

Earle’s whole-hearted embrace of theater has the songwriter as happy as ever to be in New York, where he lives with his youngest son, John Henry. The two of them recently moved from the Village to Battery Park City. After nearly two decades of living in New York, he’s proud to finally own his own apartment, which he bought with money he recently received from selling all his publishing to former Warner CEO Cameron Strang. “I sold everything,” he says. “So I’m starting over, as far as being a songwriter and having royalties and income from copyrights….I didn’t get the kinda money Bob [Dylan] and Bruce [Springsteen] got, but it was good money for me and I was able to buy a place in New York. And I’m out of debt.”

Earle has almost little time to listen to new music or read new books these days, what with all of his art, theater, television writing, and novel plotting. “I don’t get to take dope these days,” he explains, “but I re-read Harry Potter novels a lot.”

He’s also putting his all into this current burst of inventiveness. During a rare day off between dates in Dallas and Austin this July, he’ll drive his band the 14 or so hours there and back to Marfa for a day, where his dear friends Terry and Jo Harvey Allen will be celebrating their 60th wedding anniversary for two weeks.

“I gotta be there for that,” Earle says. After the losses of Van Zandt, Clark, and now Jerry Jeff Walker, perhaps it’s more important than ever for Earle to be celebrating his friends and mentors while they’re still thriving. After all, no one has ever accused him of not respecting his elders.